reams were her gift. Every morning, she'd wake up and tell her husband, Al, how she'd dreamed about angels or daughters or catastrophe. Good or bad, she'd always wake up with a story to tell -- until the day she never woke up at all.

Al never had that gift. His dreams were vague, or they'd escape him 20 seconds into his day. He had nothing to jot down like she did, nothing to file away for a conversation over dinner. Even after she died some 11 years ago, he never dreamt of her, could never summon her back into his subconscious. This frustrated him to no end, because, once he was awake, all he did was daydream about her.

But then, about 10 weeks ago, in the middle of his deepest sleep, Al Joyner finally saw Flo Jo. She had driven up in a car, smiling, and strolled casually toward him. She was stunning, as always, and wore her hair in a bun, just the way he'd always adored it. He asked her, "What are you doing here?" And her response was, "I'm just coming to check on you." He didn't know what to say next. Their daughter, Mary, was about to graduate from high school, and he wanted to ask, "Are you here for graduation?" But before he could speak, his alarm clock went off.

The buzzing jarred him, and his dream was barely intact now. He could see her leaving, climbing back into her car, smiling again. He wanted more, wanted a full-blown conversation, but an instant later, Al was awake, the moment over.

He sat up in bed, both agitated and wistful. That was it? That was the whole dream? He hadn't finished. There was so much to tell her, about him and Mary and premonitions that had come true. There was also news to share, news she'd probably beam about.

The next night, he went to bed early, hoping Flo Jo would reappear, hoping the dream would pick up where it left off.

But when he woke up, nothing. He wanted to punch his pillow. Nothing.

An agonizingly slow start

She has just been in the air these days, in the ether. Twenty-five years ago this month, Al Joyner won a shocking gold medal at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles … and fell in love with a lady in tights. He has tried to move on with his life, but 25 years is 25 years, and he has begun to sense her again, in the wind, in his mind, as if it were yesterday.

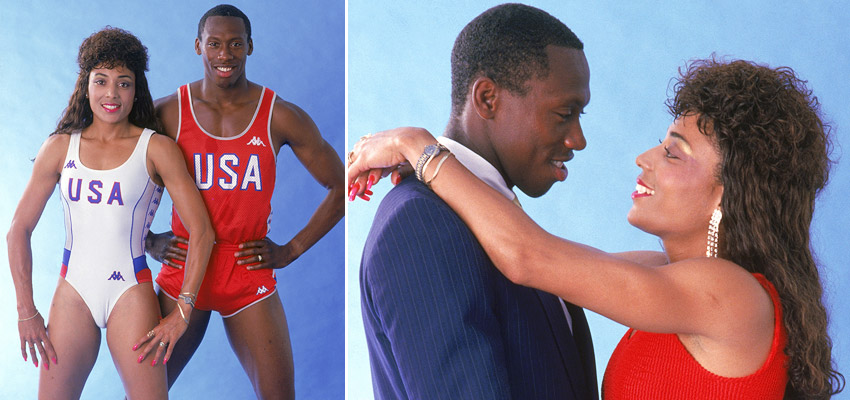

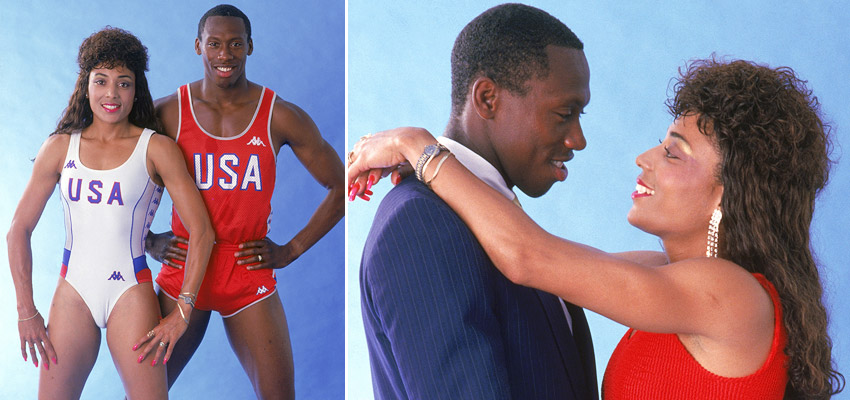

Kevin Winter/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Florence and Al Joyner were track and field royalty.

Just in July, for instance, the L.A. Sports Council invited Al and many of the 1984 medalists back to the creaky Coliseum, where one by one they were welcomed by raucous applause. If it wasn't Mary Lou Retton, it was Edwin Moses. If it wasn't Greg Louganis, it was Bart Conner. The audience heard tales of Mary Decker and Zola Budd, Michael Jordan and Bobby Knight. But as Al roamed the grounds and stared at a freshly lit Olympic flame, another story kept rushing back to him, a mystical story no one really knew about, a story he was dying to share: the story of Florence and Al.

He had first laid eyes on that woman in 1980, at the U.S. Olympic trials in Eugene, Ore. He can still remember the time (7 p.m.), the place (a sign-in table), their ages (both 20) and her face (gorgeous). She looked so elegant, he assumed she was a trainer. He was wrong.

He asked for her name, and she told him, "Florence." He told her his, and that was the extent of their conversation: an insecure man and an introverted woman literally passing in the night.

The next day, he saw her warming up for the 100 meters and did a double take. He asked around, and learned she was a UCLA sprinter who would soon be teammates with his talented high school sister, Jackie Joyner. He rushed to find Jackie, who was warming up for a race herself, and said, "Jackie, there's this girl from UCLA named Florence Griffith, and you need to find out if she has a boyfriend."

"Yep, she has one," Jackie said.

"Well, if they break up, let me know."

"She's not going to like you."

"What do you mean, she's not going to like me?"

"Because I don't like you."

That didn't stop Al from digging. He found out Florence's boyfriend was an 800-meter runner, David Mack, and although Al turned sheepish and never spoke with her again in Eugene, he pasted Florence's UCLA track photo onto his bedroom wall at Arkansas State.

"I had a girlfriend back in Arkansas who said, 'Why do you have a picture of this girl?'" Al remembers. "And I said, 'That's the girl I'm going to marry.'"

Al gets the gold, not the girl

Al's hope was to romance Florence at the '84 Olympics. He had it all mapped out: He'd wine and dine her, sweep her off her feet. But then everything changed in January '81: His mother died.

Mary Joyner was only 37 years old when she contracted a bacterial infection that led to a massive hemorrhage of her adrenal glands. When Al got to her, near his hometown of East St. Louis, Ill., she was in a coma with no discernible brain activity, her head swollen to twice its normal size.

Because Mary had been estranged from Al's father, and because Al and Jackie were the oldest of Mary's four children, the two of them had to decide when to turn off the respirator. Al had never really faced death until then, and it was excruciating to say goodbye to her. Mary had been strong and beautiful herself, a former nurse who had chased Al off the streets, who had urged him to maintain his job as a shoe-shiner. She'd wanted him to be trustworthy, and, one day, as a teenager, he ended up rescuing a little girl who had been drowning at a local pool. The little girl returned the next day calling Al, "sweet man by the water,'' and soon that became his nickname: "Sweetwater.'' Mary loved what her son was becoming. She'd tell Al, "Make sure your words are always sweet as honey, because you never know when you'll have to eat 'em.'' It's why he was so popular. She taught him how to be a gentleman, and, even though his sister was the more acclaimed athlete, his mom often had said, "One day, Al will shine brighter.'''

So, as Al watched his mother come off life support, watched her turn cold and die, he made a pact with himself: win the '84 gold for mom, make all his training pay off.

Bob Thomas/Getty Images

Joyner on his way to gold in the triple jump at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.

Before the '84 U.S. Olympic trials, he flew to Los Angeles to prepare with UCLA coach Bob Kersee and his squadron of athletes. Al slept on the floor of Jackie's apartment, took a bus daily to Westwood and vowed not to be distracted by that beautiful woman again.

But he couldn't help but fall in love with Florence Griffith. He'd get the sweats whenever he saw her -- "I was so nervous around her" -- and he liked that she wasn't a mischievous partyer. The truth was, she was something of a loner, an eccentric. As a child growing up in L.A., she wore mismatched socks and rode a unicycle to school. She wore one braid up and one braid down, did walking handstands around the block. She was called "Dee Dee," but she also answered to "Jackrabbit," because she'd annihilate people in footraces. Her speed provided her with self-esteem, but still, as a young adult, she was a bit of a recluse.

By the '84 trials, she had a new boyfriend: Olympic hurdler Greg Foster. But most nights, Al noticed Greg flirting with other women. It galled Al, to the point where he confronted Foster.

"Where's Florence?" Al asked him.

"Up in the room."

"Greg, I don't know why you're down here talking to these other women when you got the most beautiful woman upstairs."

"What?"

"Greg, if you ever let her go, she's going to be mine."

After that, Al bit his lip. He was too focused on his gold medal to court Florence now, and simply hung around the group. Florence had no sense of his crush -- "To her, I was just Jackie's nice brother," he says -- and he became a master at bumping into her. One day, at the Olympic training camp in Santa Barbara, Florence was about to drive off in her new red Nissan 300ZX with teammate Alice Brown, when Al flagged her down.

"Can you give me a lift?" he asked.

"It's a two-seater," she said.

"I'll lie down in the hatchback."

"OK."

He would've happily stood on the roof, just for the chance to ride with her, and if the other athletes had been paying closer attention, they would've seen through him. He purposely walked with Florence to the Team USA photo in the Olympic village, and in the days before her 200-meter final, he was asked by Valerie Brisco-Hooks (Florence's main competitor) to predict a winner. "Florence," Al had said instantly.

It didn't pan out that way. Although Florence won every preliminary round, Brisco-Hooks flew by her in the finals. Al felt badly for Florence, but he had his own event to tend to. He was a triple-jump afterthought, expected to be the third American behind Mike Conley and Willie Banks. And when he tweaked his ankle in his first qualifying attempt and botched his second, his entire Olympics boiled down to a third all-or-nothing jump. But he channeled his mother, tempered his breathing and jumped 55 feet, 9½ inches to put him into the next day's finals.

He went to bed that night refreshed. He called his college coach and said, "All I have to do is wake up tomorrow -- and go get my gold medal."

The next day, his first jump was free and easy -- a lifetime best: 56-7½. Suddenly, the heat was on everyone else. His good friend Conley fouled on a last attempt to catch him, while Banks, a Southern California native who had the Coliseum crowd behind him, kept mistiming his leaps. Al had the gold, in arguably one of the biggest upsets of the '84 Games.

During the medal ceremony, he thought of his mother. He'd woken up and gotten his gold medal; why couldn't she have woken up from her coma? As he listened to the national anthem, that's all he could think about: What's so hard about waking up?

He felt alone. Florence had barely batted an eye at him yet. He felt utterly alone.

The first premonition of death

He was about to leave L.A. for Arkansas when he sidled up to Florence for a goodbye: "If I ever come back to California, will you show me around? Show me Disneyland?"

Her answer was "Yes, OK," and he later sent her a Christmas card along with one of his promotional photos. She sent him back a picture of herself with her silver medal -- and, for the first time, he had a sliver of hope. He began mailing her friendship cards that were borderline sappy. She certainly knew of his crush now, and by 1986, he flew to L.A. to train for the '88 Olympics with Jackie -- and to put the full-court press on Florence.

"I told everybody in Arkansas the only reason I won't come back is if I marry Florence Griffith," Al remembers. "And they said, 'Well, we'll see you soon.'"

Tony Duffy/Getty Images

Joyner didn't want to ruin his chances at a relationship, so he backed off for a while. Florence later called and asked him out.

He arrived the week of Halloween, and purposely drove by the bank where she worked. She was decked out in her costume -- a wedding dress -- and Al couldn't resist saying: "Oh, you're ready to marry me?"

She gave him a playful yes, to which he replied: "You know how serious I am, right?" She laughed, then changed the subject. He reminded her of her promise to show him L.A., and she claimed she hadn't forgotten. The courtship began.

He found out she worked out at a local Bally's fitness center, so he joined the club himself. "Cost me 600-some dollars," he says. They began going to dinner and listening to music at her apartment off Florence Avenue in L.A. She liked Anita Baker records, so he bought some, too.

He started to stay up late with her, while she'd braid people's hair or manicure people's fingernails. Her interests far exceeded track and field. She loved arts and crafts, and sewing and constructing handmade children's mats. Most of the time, she'd be up until 2 or 3 a.m., dabbling in her hobbies, and Al patiently sat with her, although he knew they'd end up overtired.

Eventually, he told her to get more rest and to stop eating at McDonald's. She wasn't insulted and asked him, point-blank, "Al, how did you win your gold medal?" He told her he believed in himself when no one else would, and that struck a chord with her. People neverbelieved in her, either. Some called her the "Silver Queen," because she'd had a spate of second-place finishes. So Al told her he believed in her 1 million percent -- and that's when he realized he'd better back off.

"I had to stop calling her," he says. "I thought about high school and how girls I'd be out with would all of a sudden want to be just friends. I didn't want to ruin the relationship. So I just stopped. Stopped being around her, stopped practicing with her."

Weeks later, while he was staying with Jackie and her coach-husband, Bob Kersee, in Long Beach, the phone rang. It was Florence, looking for Al. She asked him out.

They drove to a nightclub with one of Florence's girlfriends. It didn't feel like a date. But every time another man asked Florence to dance -- and there were about 50 taps on her shoulder -- she said no. She'd dance only with Al, and from then on, they were serious boyfriend-girlfriend. She reminded him of his mother, while Al reminded her of nobody. "Because no one has ever treated me as well as you," she told him. "You really are sweet man by the water.''

They had a favorite song, "All My Life" by K-Ci and JoJo, and Al couldn't believe how much the lyrics fit them: "Girl you are ... Close to me -- you're like my mother. Close to me -- you're like my father. Close to me -- you're like my sister. Close to me -- you're like my brother. All my life I prayed for someone like you. Yes, I pray that you do love me, too."

He decided to propose, and the only question was when. Al was a numbers man, and when it came to Florence, he'd decided his lucky number was seven. He had met her seven years before at 7 p.m. She was the seventh of 11 children. Their next date was on July 17. It was 1987. So that became his plan: propose to her at 7 p.m. on 7/17/87. "If she was going to say no, it had to be on all my lucky numbers," he says.

He booked a limo and made reservations at the trendy Brown Derby restaurant. But when he arrived, she had curlers in her hair. "Why a limo?" she asked him. "I just want to go to McDonald's." He begged her to just drive with him, and when the song "Stand By Me" came on the radio, he said, "You're the most beautiful, straightforward woman I know. Will you marry me?"

They set their wedding date for late 1988, after the Olympics. But on Oct. 1, 1987, Florence was horrified by a Los Angeles earthquake that registered a magnitude of 5.9. She grabbed Al by the shirt and said, "Let's go. I don't want to die without being married."

She had never spoken before about death, and she seemed serious, agitated. It shook Al a bit, so he drove her to Las Vegas for a quick, impromptu Oct. 10 wedding, nine days after the quake.

She wore her Halloween wedding dress.

Tony Duffy/Getty Images

Florence Griffith married Joyner in 1987.

Track & Field's first couple

The married couple soon could be seen sprinting down Victory Boulevard, near their home in Van Nuys, Calif. And that was the whole idea -- so Florence could envision victory.

Before their marriage, she seemed to lack a certain race-day arrogance, and as her new full-time coach, Al stepped up the positive reinforcement. He got her to bed early -- no more marathon nail sessions -- and monitored her diet. She was eating mostly fish and chicken, taking vitamins, drinking more water. In the gym, she was doing squats, lunges and every other leg exercise under the sun. Her philosophy was "To run like a man, you have to train like a man." But when she showed up chiseled at the '88 U.S. Olympic trials in Indianapolis, the whispers reflected exactly that: masculine … testosterone … steroids … cheat.

While Al steamed, she ignored it -- and

set the world record in the 100 meters with a 10.49.

Ten-four-nine! The track world was so stunned, critics claimed it was wind-aided, or the clock had malfunctioned. They pointed out she hadn't even been a top-10 sprinter in 1987 and doubted she could knock 0.27 of a second off her previous best legally. She had run as fast as Jesse Owens in 1936 -- the equivalent of a 9.5-second 100-yard dash -- and faster than some current international men's champions. Not only that, she had raced with her hair down, wearing a risqué, purple one-legged bodysuit -- an athletic negligee, she called it. She'd also worn her fingernails 4 inches long, colored immaculately. She was a modern star -- Flo Jo -- celebrated and ridiculed simultaneously. But her drug test came back clean, and even though there was evidence of a late breeze in the race, her 10.49 stood.

She and Al were on cloud nine. Before the trials, he had spent months building her up, teaching her how to run relaxed, giving her motivational books, writing "Gold Medal" on the walls of their home. He'd work her out at 4 a.m. sometimes, and she even defeated him in a race one day, prompting him to say, "No woman will beat you -- you'll run a 10.5." Her response was "Al, have you lost your mind? If I run that fast, they'll dissect me." She wasn't lying.

AP Photo/Rusty Kennedy

Flo Jo reflects on her world record in the 200-meter finals at the 1988 Seoul Olympics. She won in a time of 21.34 seconds.

As the accusations increased, Al's instinct was to lash out. But she'd hush him, the way his mother used to. She'd say, "If I stop to kick every barking dog, I'm not going to get to the places I need to go." Or she'd tell him, "Al, you know how hard I trained." She still had gold medals to win, more bodysuits to design.

In Seoul, at the '88 Summer Games, she was the world's hottest name. Despite getting off a bus with legends Edwin Moses, Evelyn Ashford and Steve Scott, she was the one who was bum-rushed by fans. And she lived up to her billing. Again racing with her hair down, she swept the 100 and 200 with a wind-aided 10.54 and a world-record 21.34, respectively. She later won a third gold in the 4x100 relay, and constantly hummed "The Star-Spangled Banner," her new favorite song.

After Seoul, the daggers continued to fly. Critics claimed Flo Jo wore heavy makeup to hide steroid-induced acne, and an 800-meter runner, Darrell Robinson, told a German magazine, in a paid interview, that he had sold her human growth hormone six months before the '88 Games. He claimed she had slipped him 20 $100 bills and that she'd said, "If you want to make a million dollars, you've got to invest some thousand dollars."

Flo Jo couldn't bite her lip any longer. She went on the "Today" show and called Robinson a "crazy, lying lunatic." Years later, Robinson's credibility would take a hit when he tried to commit suicide by drinking antifreeze. But the damage was already done. A melancholy Al urged Florence to turn back to her hobbies. She'd never wanted to be a career sprinter, anyway. Her goal had always been to win one gold medal. She'd always wanted to act, design clothes, stay up late, color hair, become a cosmetologist. And so, by February 1989, Al thought she should just get on with the rest of her life.

Because the track season was about to begin -- and she hadn't trained a second -- she decided to retire at age 29. The cynics said she was dodging new out-of-competition drug testing, but Al says that's false, that there was a more logical, overriding reason. In fact, he will tell you that in New York City, the day of her announcement, Flo Jo went out shopping.

For baby clothes. Little girls' baby clothes.

Then along came Mary

A closet, tucked away in a spare bedroom, began to explode with dresses. There were pinafores and jumpsuits and UCLA cheerleading outfits, all ready for a tiny, crawling daughter. Down the hall, there was a den full of dolls, play kitchens and little pink strollers. "We had a hope chest that turned into a hope room," Al says.

There was just one problem with all of it: Florence wasn't pregnant. She'd simply assure Al that she'd soon be having a baby girl, and that this girl would be an extraordinary singer, the one talent Florence wished she'd had. It seemed curious and presumptuous not to buy a single item of boys' clothing, not to buy one truck, but Al sensed Florence's conviction and knew not to chide her.

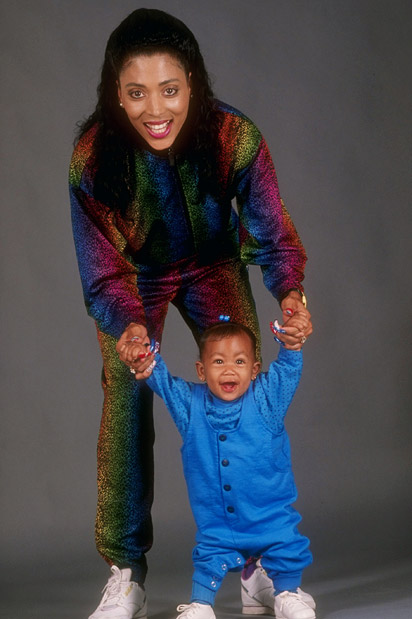

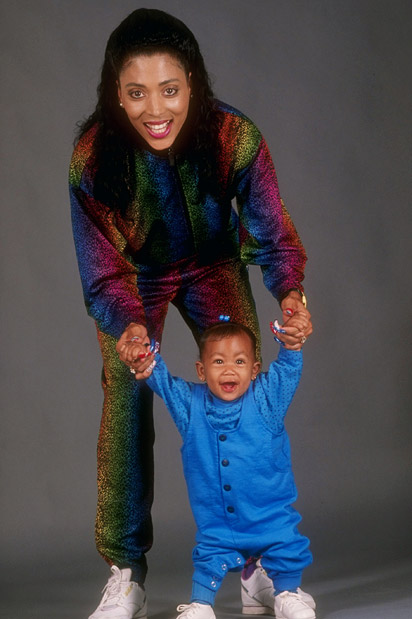

Courtesy Al Joyner

Mary was born Nov. 13, 1990.

A year later, she finally was pregnant, and Al noticed how much she glowed. She'd eat whatever she wanted, guiltlessly, and no longer felt the urge to head to Bally's. After years of toning her body, Florence gained 63 pounds during her pregnancy. "I called her 'Prego,'" Al says.

She gave birth on Nov. 13, 1990 (with makeup on) to -- what else -- a healthy baby daughter. It amazed Al a bit to see how clairvoyant Florence had been, but it wouldn't be the last time, especially when the little girl began to sing.

Florence had named the child Mary -- to honor Al's mom -- and by age 2, little Mary was already belting out, "The Star-Spangled Banner." The toddler couldn't speak complete sentences yet, but she could belt out her mommy's "Olympic song," which had Al speechless. Mother and daughter were inseparable, and by the time Mary was 2½, Florence would sit her down at the kitchen table and teach her the ABCs. Florence would break out books, flash cards and shapes to quiz Mary all morning, before they'd head out to the track in the afternoon.

That was little Mary's first sandbox: the long-jump pit. While Florence was training other runners or doing wind sprints herself, Mary would dig up the pit with her tiny shovel. Before long, she began to do knee pumps and jump-rope drills with the sprinters, and Florence told people only one person was capable of breaking her records: Mary.

Before long, Florence was a soccer mom, chauffeuring Mary to gymnastics classes in their new hometown of Mission Viejo, Calif. Florence kept hand-made signs in her car, so she could flash "Your headlights are on," or "Your gas tank is open" to other drivers. Who thought of things like that? But Florence was happy in her domestic life, setting up arts and crafts booths at swap meets and doing her friends' hair and nails. You'd have never known she was an Olympic champion, except for the two times a day she'd peer up at the clock and say, "Look at the time; it's 10:49."

Al's lucky number might have been 7, but Florence had adopted 10-4-9, her world record in the 100 meters. It didn't matter whether it was a.m. or p.m.; Florence had a sixth sense to look up and locate the clock at the stroke of 10:49. She never had to be reminded or prompted; it was just one of her eccentricities. She'd simply smile and say, "What time is it, people?" and move on with her day.

Al had long known about Florence's quirks and had always considered them endearing. When she'd travel overseas, she'd write Mary exhaustive letters, so the girl would have mail waiting for her every day. But, soon, it was a little over the top. Florence would even sit down at home and write letters to her daughter, sealing them and scribbling: "Do Not Open Until You're 16." Al dutifully packed them away, thinking it was Florence just being Florence.

But then came some darker moments, some premonitions that were somewhat difficult for Al to digest. One morning, after she'd watched the movie "Ghost" the previous night with Mary, Florence woke up desperately grabbing for him.

"Al, I had this dream and you were crying," Florence said. "And I was telling you I was all right and everything was fine, but I couldn't reach you. But I was telling you everything was fine. I just couldn't get to you. You should know this."

Tony Duffy/Getty Images

Even as a toddler, Mary delighted her parents with her singing.

Her dreams had long been colorful and vivid, but now there seemed to be a certain distressing element to them. She woke up another morning sobbing, and when Al asked her what was wrong, she said, "I don't want to leave Mary without a mother."

"Well, I don't want to leave her without a father, either," he said.

"No, seriously," Florence said. "If something happens to me, I want you to get married again."

"Come on, forget it," Al said.

"No, seriously," she snapped.

He tried lightening the moment, and told her, "Well, if something happens to me, you can't get remarried. I'll haunt you."

But she wasn't budging. She said this was a crucial conversation, that she was sick about this. So he told her, straight-faced, "I'll never marry again, no way." He meant it. He used to tell people he and Florence argued about only two things: who loved the other more and who could clean the kitchen better. He told her there was no other woman for him, but Florence began wagging a finger at him.

"No, you will get married again, because I'll be the one to send her to you," she said.

"How will I know?" he asked.

"You'll know," she said.

"Come on, how will I know?"

"You'll know, Al. You'll know."

Periodically, Florence would reprise the conversation, telling Al maybe it was better if they all died together, because no one could take care of Mary better than they could. He chalked this up to Florence's creative mind. She wasn't ill, as far as he knew. She had suffered an apparent seizure in 1996 while flying to St. Louis on business, but there'd been no lasting complications or reason for concern. She was busier than ever. Not only was she writing a book called "Running for Dummies," she also was planning to open a salon and training to run marathons. Her plan was eventually to do a 30-mile jaunt, and by 1998, she already was running 22 miles in 2 hours, 46 minutes.

Mary would jog or ride her bike alongside her, which thrilled Florence to no end. Mary was already a promising athlete and could long-jump between 7 and 8 feet. She was mature beyond her years, already in third grade by age 7, already able to play the piano by ear. Florence wasn't about to push her into anything, but it seemed Mary preferred gymnastics most of all. She competed for a club team called "The Little Guns," and Florence was one of the team moms. Soon, Mary was talking ad nauseam about an upcoming meet in Santa Barbara against elite competition. Al and Florence wouldn't dare miss it, and on Sunday, Sept. 20, 1998, they drove the 100 miles to watch her.

Little Mary ended up taking first place in the balance beam and second in the vault. With her parents grinning, she stepped up on a podium -- her own "Star-Spangled Banner" moment -- and bowed down to receive her award.

The next morning, Florence was dead.

Sudden death

Florence never woke up from her last dream. That's about the simplest way to put it. Those final hours -- from gymnastics meet to 911 call -- are etched in Al's mind, and if he's told it 100 times, he's cried 100 times.

When they returned from the meet, Al went to an office he kept near their home in Mission Viejo to review an endorsement proposal for a hair product. He came home late and shot up to the upstairs bedroom to say goodnight to Florence. She already was curled up in bed with Mary, who slept in their room every night, and Al's only words were "I love you." Florence answered: "Love you, too."

AP Photo/Susan Sterner

Flo Jo had announced in June 1996 that she would not seek a spot on the U.S. Olympic team because of Achilles tendinitis. A little more than two years later, she was gone.

He would've climbed into bed with them, but he says he had a craving for ice cream and didn't want Florence to smell it on his breath. She had been razzing him about getting back into shape, and he knew the ice cream was a no-no. So he says he devoured the ice cream downstairs, lay down on the couch and fell asleep.

In the morning, he heard the ringing of their alarm clock, and walked upstairs to rouse the ladies out of bed. Florence used to purposely keep the alarm on Al's bedside table because she hated early mornings and would do anything to prolong a dream. So Al thought she was letting the alarm ring "to be funny." But this also was a school day for Mary, and Al plowed into the room to say, "Come on, we're running late."

Neither of them budged. It confounded him, so he moved closer. He could see that Mary's eyes were shut and that her legs were resting on top of Florence, who was face-down. He then tried rustling Florence out of her sleep, and when Florence still wouldn't move, he flipped her over. Her eyes were wide-open and motionless.

He screamed, waking Mary. With Florence in his arms, he told Mary to call Florence's mother on a downstairs telephone. He then dialed 911, howling, "My wife's gone. My wife's goooone." They asked him to perform CPR, and, being a former lifeguard, he was more than capable. But there was nothing close to a pulse. Sobbing, Al began to speak to Florence, telling her, "This is not the way the story is supposed to end. I'm supposed to go before you. You're supposed to watch Mary grow up, see what she's going to turn out to be." Right then, Mary bolted back into the room, asking, "What's wrong with Mommy?" And before Al could answer, the paramedics arrived, followed by a coroner.

Al and Mary were shooed out of the room, and 20 minutes later a paramedic brought Florence's wedding ring to Al, along with a nail they had broken, one of Florence's 4-inch-long painted nails. Al put the nail in his pocket.

Before long, they were bringing Florence down the stairs in a body bag. Al ushered Mary to a side room, then watched the gurney emerge. He says the coroner was crying.

Helicopters and TV crews hovered outside -- because Flo Jo was dead at 38 -- but all Al could think about were Florence's dreams, those elaborate, foreboding dreams. He instantly recalled the one in which she'd been trying to tell him she was OK, but couldn't find him. He realized she'd been trying to prepare him for this moment.

It felt like his mother's death, and he found himself thinking again, "What's so hard about waking up?'' He blamed himself for not sleeping upstairs that night -- "I might've saved her,'' he says -- and he sat the rest of the day in shambles, remembering their runs down Victory Boulevard. Eventually, something flashed into his scattered, flustered mind, something he found curiously symmetrical. He'd met Florence Griffith 18 years before at 7 p.m., and he'd found her dead, next to their 7-year-old child, at 7 a.m.

Seven, he decided, was now his unlucky number.

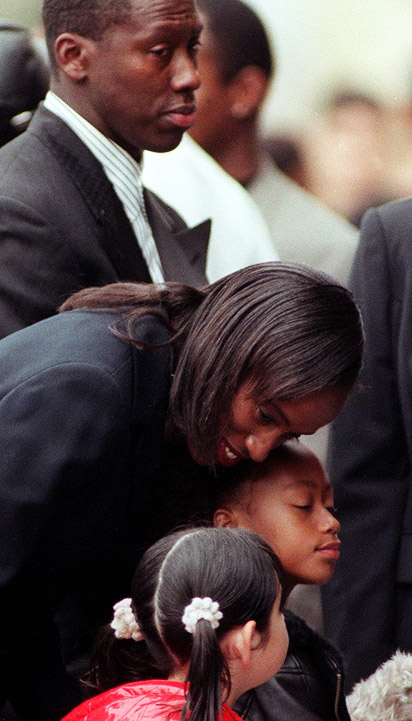

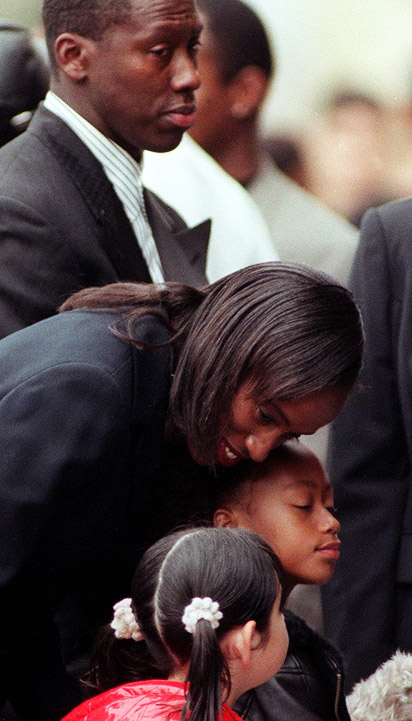

AP Photo/William Wilson Lewis III

While pallbearers carry Flo Jo's casket after the funeral Sept. 26, 1998, Al Joyner holds Mary, next to his sister, Jackie Joyner-Kersee.

Mary's life-saving decision

Florence's family wanted to take Mary away from that house immediately, but Mary wouldn't leave. "I'm staying with Daddy," she insisted.

When he thinks back on it, Al says "Mary saved my life," because in those initial hours, he says he wanted to kill himself -- "so I could catch Florence." But Mary's presence alone, her pristine face, gave him a reason to continue living. "No telling what I would've done," he says.

He kept waiting for Mary to cry, but, peculiarly, she didn't. She'd always been a weepy child, but whether it was denial, or pure shock, Mary decided she had to be "strong for my dad." At the funeral, she and a friend sang a gospel song "The Wind Blows on Me," and she stayed composed. Even after Al had his and Florence's song, "All My Life," played at the service, Mary didn't weep. When the pastor asked her whether she'd like to have the casket opened so she could say a final goodbye to her mom, Mary answered: "No, let everyone see her." So 2,000 people paraded up for a viewing, she and Al bringing up the rear.

A concerned Al waited and waited for her to wilt. He slept on the floor of her bedroom every night and kept her home two weeks from school. On her first day back in the third grade, her teacher called Al, midday, and Al figured, OK, she's finally broken down. Instead, the teacher told him that his daughter was OK and that Mary wanted to make sure he was OK, too.

Gerard Burkhart/AFP/Getty Images

Joyner's sister, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, comforts Mary, then 7, after her mother's funeral.

He wasn't OK, not even close. He kept Florence's broken finger nail in a box, and says he wouldn't sleep in the master bedroom, "because it wasn't the same -- she wasn't there. All I would do is look up and I would think she was going to come through that door. I was waiting for her to come through the garage. I was looking in the kitchen. But it wasn't happening; it was never happening."

He needed time alone, to deal with the autopsy and the media crush. By late October, the sheriff-coroner's office announced Florence had suffered an epileptic seizure brought on by a congenital abnormality in her brain. Her body had locked up while she was sleeping facedown, and she had suffocated in her pillow.

Quieting all the cynics who were assuming her death had been heart-related due to steroid abuse, the announcement was a victory of sorts -- at least to Al. Florence had been dissected, all right, and Al's comment was, "She took the ultimate drug test. I told them to test for everything. And there was nothing there, and there never was." Her detractors pointed out that there wasn't enough urine in her bladder to test for steroids, and that there were signs of heart abnormalities. Al wanted to scream "Let her rest in peace," and was worried all the negativity would seep its way to Mary. The girl still hadn't cried in front of her father, and he knew there had to be a frightened child in there, somewhere.

Of course, she was a mess. She just didn't want Al to know it. That first day back at school, she actually had burst out crying, and asked her teacher for a tissue. She then wrote a letter to heaven that began: "Dear God, is it true that my mother passed away? If so, can I have her back for just one more year?" Another time, at home, she locked herself in the bathroom, sobbing. Florence's niece, Darnesha Griffith, a track star at UCLA, had been taking care of Mary that day, and persuaded Mary to open the door.

"What's wrong, Mary?" Darnesha asked.

"Well, I watched the movie 'Ghost' with my mom," Mary said, "and I need to ask you a question."

"What?" Darnesha said.

"Is my mom going to kick the can? Like the ghost, Patrick Swayze, kicked the can?"

Weeks later, Mary was finally sobbing in front of Al, too. They had been driving on the freeway one day when she burst into tears and asked, "If anything happens to you, who'll take care of me?"

"I'm not going anywhere," Al told her, and father and daughter became inseparable. On her first Mother's Day without her mom, Mary made cards for both Florence and Al. Her note to Florence read "Mommy, be proud of Daddy, he's started training again." And her message to Al was "I love you, Daddy." Al became a playground attendant at her school, a class dad. He took her to late-night movies. Whenever the clock turned 10:49, he'd tell her, "Mommy's saying hi." They slowly began to adjust.

He began coaching at UCLA, so he gave her a cell phone when she was only 8, urging her to call him anytime, any place. He'd leave practice early to relieve Mary's nanny, or he'd bring Mary to practice with him, pointing her toward the long-jump pit.

In fact, Mary decided to quit gymnastics and asked Al to start a track club for her. She had an easy stride and began hurdling chairs and limbo sticks in their living room. Al gave her Florence's gold medal from the 100 meters, but curiously, she didn't want to flaunt her talent or draw attention away from her friends. And when Al suggested she get up at 4 a.m. to train -- the way Florence used to -- she wasn't enthused. Track and field began to fluster her.

"People'd say, 'Oh, of course you run,'" Mary says. "It was just expected. You have an Olympic dad, an Olympic mom, an Olympic aunt and a cousin [Darnesha] who won the indoor and outdoor [titles] in the NCAAs. You feel like you've got to do something with track. You'd better be good, or else you're kind of letting the name down. And that's what I had trouble with."

Then, one morning, Mary awoke recalling a dream: She'd been in a major gymnastics competition, in front of a large throng, and she'd been the star. She mentioned this to Al and said, "Daddy, I want to do gymnastics again."

It floored him. Not that she'd picked gymnastics, but because of her elaborate dream. He braced himself.

Mary had the gift.

Courtesy Al Joyner

Mary has been in the spotlight at times during her young life.

Mrs. Right, delivered by Flo Jo

Four years later, Al was still mourning, and he looked it. He was always tired or famished, and friends told him he couldn't help Mary unless he helped himself. His male friends urged him to go out at night and mingle -- with the opposite sex.

He had a hard time going down that road. He remembered Florence begging him to remarry, remembered her saying she'd send him a sign when Mrs. Right appeared. Was he supposed to find a lady with a December birthday, like Florence's? Someone with long nails? He was perplexed.

Courtesy Al Joyner

Al remarried in 2003, exchanging vows with Alisha Biehn.

One night, a buddy talked him into a night on the town, and he struck up a conversation with an attractive blonde who was a runner herself. He hadn't told her his last name, but she began raving about Flo Jo and Jackie and said it was sad what happened to Florence. It was eye-raising, but Al didn't consider it a sign.

Her name was Alisha Biehn, and when he eventually admitted who he was, he was impressed she didn't seem threatened by his storybook love with Florence. "She was the first woman I'd come across who wasn't wondering, 'Could he love me that way?'" Al says.

Their dating escalated, and his friends noticed him smiling again. He took her to see the Lakers play the San Antonio Spurs one night, and, as they left the Staples Center -- and exited onto Florence Avenue -- "All My Life'' came on the radio. Alisha heard the words ("Close to me -- you're like my mother, close to me -- you're like my father") and said, "I dedicate this song to you." Al nearly crashed.

"I had a tear in my eye and I smiled," Al says. "I said, 'Wow, you're the one.' That's when I knew. Like Florence said, I just knew."

They married in June 2003, and their main worry was 12-year-old Mary. She sang at their wedding, but, deep down, she was feeling abandoned and starting to rebel. She had asked her father five years prior, "If something happens to you, who will take care of me?" And Al had answered, "I'll never leave." But now a part of him was leaving. She had to share him with a stepmom, live in a new house. She began slacking off at her new public school, so Al punished her by pulling her out of gymnastics. He then put her back in private school -- the same school she'd been attending when her mother died -- and Al told friends, "I always try to do what Florence would've done.''

He sensed Mary's life was beginning to spiral. She had run track as a freshman in high school, but when she felt she flopped at the elite Arcadia Invitational Meet, she lost interest in the sport. "She was too hard on herself," Al says. "Her mother didn't even get invited to that meet as a ninth-grader." Mary was crumbling under all the expectations, and it didn't help that, one day at school, her mother's name appeared in a math word problem: "If Flo Jo increased her 22-second 200-meter time by 0.8 percent, what would her time be?" She couldn't escape it.

Another time, on a trip to Las Vegas, Mary saw a wax statue of her mom at Madame Tussauds and wanted to faint. She began locking herself in her room, and Al knew he had to do something. So on her 16th birthday, he gave Mary five letters from Florence, five letters Florence had written to her when Mary was 2. Five letters that read "Do Not Open Until You're 16.''

Mary could hardly breathe as she read them. Because at the top of the first letter, Florence had written the time of day: 10:49.

Mary and Flo Jo, reconnected

Mary was rejuvenated. The message in those letters, in general terms, was for Mary to be true to herself. She didn't have to race to uphold the family name. Just find her passion, whatever that might be.

Mary felt a sudden mystic connection to her mother, as though they'd just sat down and chatted. In a curious way, her mother had given Mary life, from the grave, and this made Mary and Darnesha and Al all wonder how supernatural Florence actually was. "I mean, who writes letters for their kids to open when they're going to be 16, when they're only 2?" Darnesha says. "Very eerie."

Mary leaned on all of this, for the better. Al gave her Florence's old red 300ZX to drive, and Mary became almost a reincarnation of her mom. She combed her hair with her mother's monogrammed brushes and, just like Florence, found herself glancing up at a clock every morning at 10:49 a.m. "I wouldn't even have to think about it," Mary says. "I'd look up, and it'd be 10:49, and I'd feel like she was thinking of me or trying to say something. It's a very important number to me.

"I don't plan it. It just happens. Like just accidental. I won't look up at 10:48 or 10:50. I'll look up at 10:49. Sometimes I do it twice a day. It's almost comforting."

Christopher Park for ESPN.com

Al has wished Mary luck and told her he would be there if she needed help training.

Whatever Florence was whispering to Mary -- and Mary felt her presence -- the most profound change could be found in Mary's music. Suddenly, it meant the world to her. Long before Mary was born, Florence had prayed for a musically gifted daughter -- partly because Florence couldn't hold a tune -- and Mary somehow seemed to channel that prayer. "The music thing, nobody else had done that," Darnesha says. "Not her mom, her dad, nobody. She was proud of herself. She defined who she was."

Mary considered music "her therapy," and the little girl who used to suppress her tears and lock herself in bathrooms wrote and performed a stirring song on YouTube entitled "

Let Me Cry A Little." By her senior year of high school, it was clear she was comfortable in her own skin -- her mother's daughter. She posted a Christmas song on YouTube and sang several others

a cappella. Al bragged about it to anybody who would listen.

His life was fuller and busier, too. Alisha had given birth to a son and daughter, and he'd accepted a job as a track coach at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista, Calif. Twenty-five years after his '84 gold medal, this is who Al had become: father of three, and seemingly husband of two. "I know he's remarried," Darnesha says. "But Florence is still the love of his life."

The Olympic anniversary gala this July only reinforced that. As he roamed the L.A. Coliseum -- having left both Alisha and Mary at home-- he searched for Florence, for any sign of her, any message. Then suddenly someone played the national anthem -- her national anthem -- and he felt her. The people at his dinner table then watched a grown man get teary-eyed.

"I realized then how the '84 Olympics changed my life," Al says. "Changed my life because it was the doorway for me to meet my future wife. When I look back on it, those Olympics meant more to me than anything else that's ever happened in my life. And being there again was overwhelming, joyful and sad. I thought I'd let Florence go. But that night let me know I had not let anything go. It made me wish I could see her. I found myself standing exactly where I got my gold medal, and I felt exactly how I felt 25 years ago: alone."

Mary, lucky Mary, seemed to be able to channel Florence -- much more easily than Al. At her high school graduation, he had told Mary, "Mom would be proud of you," and Mary had answered, "She is." Who knows what Mary has heard from Florence, or thinks she's heard? Who knows what Mary has dreamt? But a couple of weeks before the anniversary gala, 18-year-old Mary pulled Al aside and gave him stunning news: She was getting back into track.

"I just feel like I'm destined to, I guess," she says. "If anyone has the genes to reach my mom's potential, I guess it's me."

Al wished her luck and told her he would be available if she needed help, if she needed a partner, if she needed someone to run down Victory Boulevard with her. Mary is trying to do this under the radar -- and sometimes she gets cold feet -- but her hope is to slowly ease back into shape and be ready to sprint and long-jump for Santa Monica College this September. She has been training periodically with one of Al's Olympic athletes, who just told Al: "She can really run. It just depends if she wants it."

So that's why Florence is in the air right now, in the ether. Al says all the time that his goal is to get to heaven so he can ask her his questions, ask her how she knew their baby would be a girl … how she knew their baby would be able to sing … how she knew Alisha would be coming … how she knew she'd die young … whether she's the one who nudged Mary to run again.

If he could lure Florence back into his dreams, maybe he'd know. All he'd have to do is wake up, and he'd have his answers. If only he had the gift. He'd trade in his gold medal if he could have the gift.

Christopher Park for ESPN.com

Mary plans to run sprints and long-jump at Santa Monica College this fall.

reams were her gift. Every morning, she'd wake up and tell her husband, Al, how she'd dreamed about angels or daughters or catastrophe. Good or bad, she'd always wake up with a story to tell -- until the day she never woke up at all.

reams were her gift. Every morning, she'd wake up and tell her husband, Al, how she'd dreamed about angels or daughters or catastrophe. Good or bad, she'd always wake up with a story to tell -- until the day she never woke up at all.